The AI Wiretap

Examining the "Rewind Pendant" and "Tab" under the wiretap theory of the internet

A few months ago, I had a series of meetings that I had to attend, and it was critical that I remember the content of each meeting. Nobody else there was taking notes and I certainly felt that I needed to, so I came up with a hack of a solution, without disruptively typing in front of everyone.

I recorded the meetings using the Google Recorder app on my phone in my pocket. The Google Recorder app is a really cool piece of software that, leveraging the Tensor chip and a proprietary AI model, can produce extremely high-quality transcriptions of the recordings. And it all works on-device, no network connection needed, and completely private from Google’s prying eyes.

At the time, ChatGPT had just released Advanced Data Analysis to subscribers, allowing users to upload .txt files to use as prompts. So, I exported the transcript from Google Recorder and fed it the unintelligible wall of transcribed text. The result was a shockingly good note sheet, and no effort on my part.

This little experiment solved a short-term challenge of mine, but also opened Pandora’s Box. Although I enabled the private mode on ChatGPT, used a local transcription service, and deleted the recordings and full transcripts later, I still felt uncomfortable about my actions. I did not ask for consent to record and knew that my little experiment was violating the assumed ephemerality the others in the meeting assumed they held. In one of them, the presenter asked people not to take pictures or recordings. I recorded anyway, anxiously.

Despite my ethical discomfort with the experiment, I continued to think about it whenever I struggled to remember something. I began to wonder about if I could turn this little shortcut I had created into a product.

Over the course of the following months, I imagined a mobile app that used always-on background microphone access, transcribed any words it heard, categorized them by the speaker, and then put them through an AI language model. Then the user could ask it any question about anything they forgot or needed explained better.

I imagined nightmarish designs, straight out of Black Mirror. One where the app sent push notifications after conversations letting the user know that they had sounded awkward or unintelligent, and exactly how. I imagined the AI suggesting to the user how they should treat people in the future, often in ways that increased the social standing or career goals of the user while hurting those around them. I imagined marketing telling users that they would be statistically more successful if they outsourced their social, career, and romantic decision making to the AI.

And over the next few months, it became clear that I was not the only one imagining this sort of a product. But perhaps I am the only one uncomfortable with it.

One startup, Rewind.AI, started a few months ago innocuously as a “search engine for your life”, with the initial product pitch being an app that collected historical data about your work and files to make it easy to retrace your steps, sort of like a better version of macOS Time Machine. And it all was stored locally on your computer, making it not any less secure than a backup drive. The product they have built is pretty cool, and probably very useful to a certain sort of sleep-deprived engineer desperately trying to remember how they got a piece of code to work last week but cannot remember now.

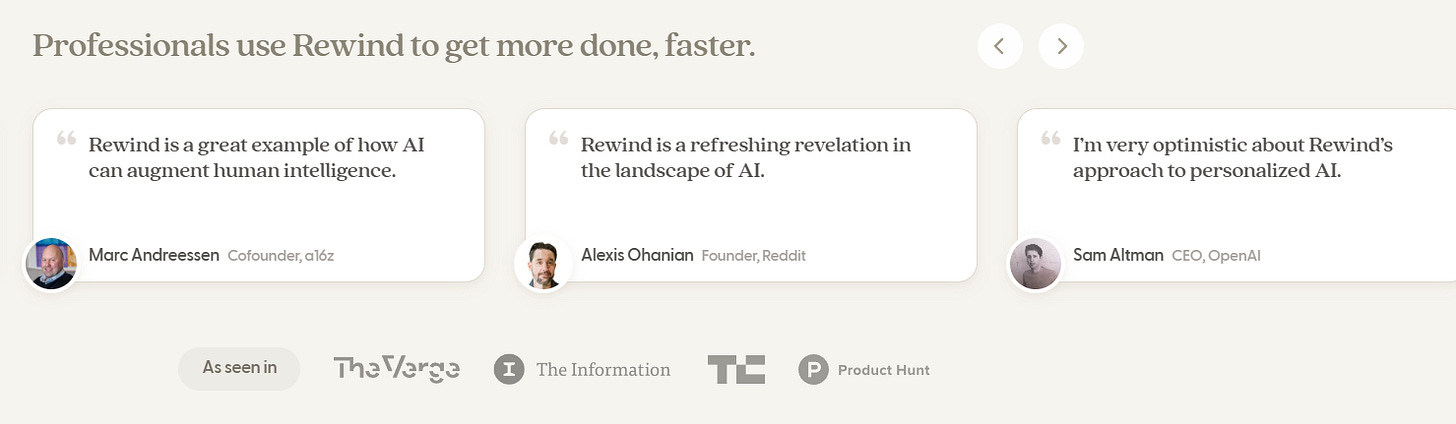

Since the explosion of GPT-3, their project has realized its potential. Now, the app puts all of your data into a GPT-4 chatbot that you can prompt. If you’re willing to waive the (temporary, solvable) security risks of having a literal keylogger connected to ChatGPT, it’s a pretty cool product. The testimonials they advertise on their landing page are quite glowing:

This is a neat product, one that I could see myself using in the future.

But just two months ago, they announced another product, one that threatens to bring my uncomfortable vision to light. The “Rewind Pendant”, a $59 necklace-mounted wearable, is designed to collect everything you say and hear.

And the very day before, entrepreneur Avi Schiffmann, famous for building ncov2019.live at age 17, announced Tab, effectively the exact same product.

These product pitches both fall head-over-heels to virtue signal about how concerned they are about the potential issues they could cause. They also offer very little in the way of solutions.

On the one hand, these are really cool highly useful products. On the other, the potential harms are highly concerning.

I am a techno-optimist. I am not a person who worries about “ethical design”, “dark patterns”, “risk”, or “trust and safety”. Unlike the overwhelming majority of people who write long essays about tech, I am actually optimistic about the future of humanity. But the more I think about the Rewind Pendant/Tab, I see its simultaneous inevitability and destiny to destabilize our most essential social norms of ephemerality and privacy.

Many people want a Rewind Pendant or Tab. A product that prevents you from forgetting anything ever is highly useful and greatly increases human efficiency.

But to a similar degree, the this device removes the ephemerality of any conversation. We live in a weird moment in human history where we now all have recorders in our pockets. Yet you safely assume that when you go up to and talk to a person their recorder is not on. And you don’t ask your friend if their recorder is on before telling them a secret, because you can assume with 99.99% accuracy that they are not recording you. I personally cannot imagine telling a friend any kind of secret while they are wearing Rewind Pendant.

While people may feel uncomfortable about the ephemerality of the conversations they have around a person wearing one of these devices, the real roadblock to adoption is the privacy concerns to the owner of the product. Both of these startups assure you that your data is stored with top-tier encryption standards that make it inaccessible to them.

This is either oblivious ignorance or willful deception on their part. Presumably the end-goal of these products would be that a user wears it their entire life, and never purges the data. Encryption standards are a perpetual cat-and-mouse game wherein algorithms are frequently created, exploits for them are found, and they are replaced. For this reason, the famous private messaging app Signal only stores message data for a very short time. And they are investing into research to make their encryption quantum-computer-proof.

And of course, let’s not pretend that encryption is some silver bullet to prevent all forms of snooping on data. After all, we live in the age of Pegasus. It should be assumed that every government has well-developed vulnerabilities to every internet-connected device.

We live in a time where the surveillance in our lives grows exponentially. The innovations of the past half-century have made life better for us all with a secret consequence. Writer Yasha Levine says in his book on the topic, Surveillance Valley,

In the 1960s, America was a global power overseeing an increasingly volatile world: conflicts and regional insurgencies against US-allied governments from South America to Southeast Asia and the Middle East. These were not traditional wars that involved big armies but guerrilla campaigns and local rebellions, frequently fought in regions where Americans had little previous experience. Who were these people? Why were they rebelling? What could be done to stop them? In military circles, it was believed that these questions were of vital importance to America’s pacification efforts, and some argued that the only effective way to answer them was to develop and leverage computer-aided information technology.

The Internet came out of this effort: an attempt to build computer systems that could collect and share intelligence, watch the world in real time, and study and analyze people and political movements with the ultimate goal of predicting and preventing social upheaval. Some even dreamed of creating a sort of early warning radar for human societies: a networked computer system that watched for social and political threats and intercepted them in much the same way that traditional radar did for hostile aircraft. In other words, the Internet was hardwired to be a surveillance tool from the start. No matter what we use the network for today—dating, directions, encrypted chat, email, or just reading the news—it always had a dual-use nature rooted in intelligence gathering and war.

And through each era of computing, we’ve had this surveillance side effect grow stronger in the shadows. According to Levine, early computers were created to help military data science. The internet was created to help intelligence offices share data.

Once it was discovered that it was also useful as a civilian tool, it was rolled out explicitly to create a way of collecting more data on how people thought, to use for military advantage.

Early social networking made it easy to surveil fringe communities and target individuals with propaganda, en masse.

The mobile era made all of that data collection a mandatory staple of everyday life, making every task today impossible without it.

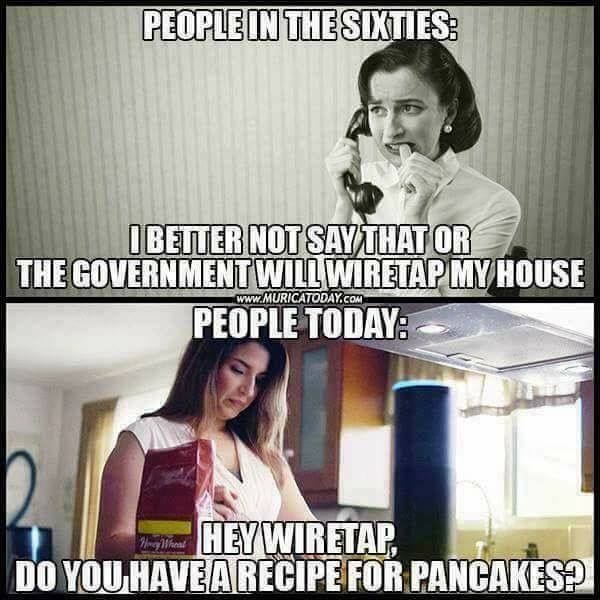

The cloud era brought all corporate and personal documents to easy view of governments. Almost every website you visit today is either running on AWS, Azure, or Google Cloud. All of that data, centralized, for easy access. It also created the digital assistant phenomenon, where it was suddenly normalized to have an always-on listening device inside your house.

Now with AI, I can already see the new world of surveillance on the horizon. With each new era of this age of computers, we have greatly improved the quality of the tools at our disposal. But we have also created a new normalized wiretapping mechanism, each one more nefarious than the last.

Rewind Pendant, Tab, and other devices of their nature probably don’t bring the same benefit to society that these past innovations have. And the cost of it is at least on par with, if not worse than the rest of them. But wearing them benefits their user, giving them a competitive advantage over their peers. If the people making these are smart, they will advertise that people who wear them are more efficient and successful than those who don’t.

I wrote this because I think we need to get the conversation rolling on when this tech is okay to use. I personally will never talk casually with somebody wearing one. And the thought of companies enforcing these on their workers to ensure efficiency sounds nightmarish. But turning one on for a meeting with consent, like how Microsoft Teams will soon add an option to get an AI transcript and notes from a meeting you missed, is probably fine.

Good luck.