How AI Will Be Monetized

From subscriptions to ads to API fees, AI has no concrete pricing model

As I covered in my recent article On the Google Antitrust Case, we are in a time of shifting technology. Google, the monopolist of search engines and web browsers, is now in the most precarious position it has occupied in its two decades of dominance. It’s not a question of if this model will change; it’s a question of how. More broadly, the industry is pivoting to create the most value out of recent AI innovations.

Right now, deploying AI tools to millions of users comes with extraordinary costs. OpenAI currently charges a high price for its models: $5 per million input tokens and $15 per million output tokens (this has been halved twice in the past year, even as the quality of the model has improved substantially). Even at this high price, OpenAI is currently nowhere near profitability.

Google just launched AI Overviews in Search, where some search queries may receive an AI-generated answer. They took an interesting path with this, using what seems to be a fast low-quality Gemini model. While this saves them from the extraordinary costs OpenAI, Anthropic, and their own DeepMind lab are incurring by serving these models. It also comes with the risk of providing a low-cost service, which, based on my experience, results in high levels of hallucination.

We are currently operating in the short term of AI. The most advanced models, GPT-4o and Claude 3 Opus, are still relatively dumb and unpredictable. Currently, they are oxymoronically untrustable and are improving exponentially. This time period is also a moment of excitement with lots of VC cash going into new startups, which will inevitably precede a bubble burst and crash.

Contrast this with the long term of AI. I estimate this to be about a decade away. In the long term, AI models far more powerful than anything we have today will be free and possibly run locally on our own hardware. They will likely be built and maintained with structures different from those of traditional corporations. They could be:

Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs) that grant access to models based on crypto donations to a network

Open source communities as they exist today

Piratical hacker collectives that do hack-and-leak operations on the leading AI companies, distributing the source code anonymously.

Nation states

It is possible that laymen will not pursue or use the frontier of models, because nothing (or little of what) they need to do requires it. The frontier of AI might return to the domain of nerds, scientists, and mathematicians. Even if the technology isn’t open-sourced due to profit motives or cannot run on consumer hardware, prices will face downward pressure as AI systems lack network effects; companies can move their systems from one API to another with extremely low switching costs. This future is, importantly, context-dependent on the fact that we don’t let regulators overzealously control AI because that would result in a cartel selling AI at high prices due to lack of disruption, and prices will have no downward pressure.

I should stress the positive nature of downward pricing pressure in AI. A world where multiple firms compete to create AIs that are more capable and at a cheaper cost will mean that to not go out of business, companies will be incentivized to make AI systems as cheap as possible. Long-term profits from AI will be zero, and the surplus value from this technology will be spread democratically amongst the users and developers who create value with it.

The much more important situation is the medium term. In this period, AI will become rapidly more useful and integrated into far more parts of our lives. AI will be highly useful and not out-of-the-question expensive (as it is now), but not free either. This is the point where AI will be most profitable. Demand for AI tools from consumers and businesses will grow significantly, and VCs will expect a return on investments currently being made.

The problem with this era is that AI cannot be given out for absolutely zero. This means that some profit model will be needed, while companies will need to do attract/extract cycles to lure in users before requiring them to pay up. How exactly to do this, is a tricky question.

Charging users for a product with an indecisive product-market fit

Most illustrative of this new business model shift in the industry is OpenAI’s ChatGPT Plus, which gives users a range of tools to utilize their best models in an accessible $ 20-a-month app subscription.

The $ 20-a-month model is slightly pricier than your average app subscription. For a representative sample of popular app subscriptions: Microsoft 365 is $5, Xbox Game Pass is $10-$17, Netflix is $15.49, and most music apps are $11. ChatGPT charges slightly above these household-name services

When asking how much to price an app subscription, the main question that arises is how much value it provides to its users The problem is that the value an AI chatbot offers varies widely among users. Some software engineers use it all-day-every-day, regularly hitting the paid ChatGPT rate limit. Most people use it on a just-for-fun basis to “check out what the new cool thing is,” with only a few chats a week. Right now, the actual functionality of these tools is minimal for the average user. The biggest areas that it needs growth are the following.

Hallucinations

Knowledge cutoff preventing the model from accessing current updated information

Safety restrictions

Lack of visual stimuli and “people also ask” popups to guide uncertain users

This is in addition to the fact that AI's main function, bringing intelligence to your fingertips, is not appealing on its own. ChatGPT is marketed as a tool, and strictly so.

Consider how the internet was originally intended to be a place for government agencies and universities to share research. A large portion of it is now composed of cat videos and pornography. The printing press was originally intended to provide every family with a copy of the Bible. The Amazon Best Seller list is now exclusively comprised of romance, fictional slop, and “self-help” garbage. Market demand driving all innovation is inevitably used to gratify our most primitive desires, and AI, unfortunately, will be no different. People want the AI girlfriend/boyfriend a lot more than they want the empathetic AI tutor.

I (and many others!) hold an instinctual aversion to the idea of romantic AI chatbots that replace human companionship, as seen in numerous science-fiction stories. Unfortunately, this seems rather inevitable. Especially in our current loneliness epidemic, AI companionship will face high demand from many people. While I remain optimistic about AI’s effect on future human prosperity, the reality remains that this will be one of its most impactful changes.

ChatGPT’s $ 20-a-month pricing currently seems to be highly based on the factor of how much consumers are willing to pay for it. It’s a middle ground between your average Joe who just wants to try out the new thing and the engineer or student who relies upon it heavily. This contrasts the appropriate pricing for somebody who falls in love with their chatbot: astronomically high. With how much people spend to woo romantic interests today, it’s not inconceivable to see people in the future spending most of their income for continued access or upgrades to their AI lover. To lean into the dystopian-ness of it all, I could imagine AI companies price discriminating to users based on how much they are in love with their chatbot, extorting the maximum value.

But there’s another form of price discrimination already being deployed, and it isn’t as sinister.

“You’re $0.0005 short of the tokens necessary to finish this sent-”

When OpenAI released GPT-3 in June 2020, it did so through an API with pay-as-you-go pricing. During this time, OpenAI still held the veneer of being a “non-profit research lab” with the insinuation that they only charged users for the equal amount of what their compute cost to provide and that it was only closed-sourced because of “safety reasons.” Nobody thinks this anymore as their model now is identical with every other for-profit lab.

Nearly every other AI company has adopted this model of pay-as-you-go APIs to sell its services to businesses. OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, Midjourney, ElevenLabs, and everybody else sell this way. None of them intend these to be used by ordinary end users, evidenced by their interface resemblance to traditional cloud service websites, which are far from consumer-friendly.

This side of the business has not been marketed toward consumers. As a user, thinking about the financial impact of every little question or prompt tweak you make drastically increases friction and anxiety around using the service. Human psychology drives people to ration scarce resources, and users will naturally gravitate away from software platforms associated with the anxiety of wondering, “Do I want to pay for this?” for every relatively small query they have.

However, this model is appropriate for businesses. Bureaucracies can rationally consider the extent to which they use resources, and a pay-per-use model gives companies rather simple criteria for deciding whether to implement an AI solution.

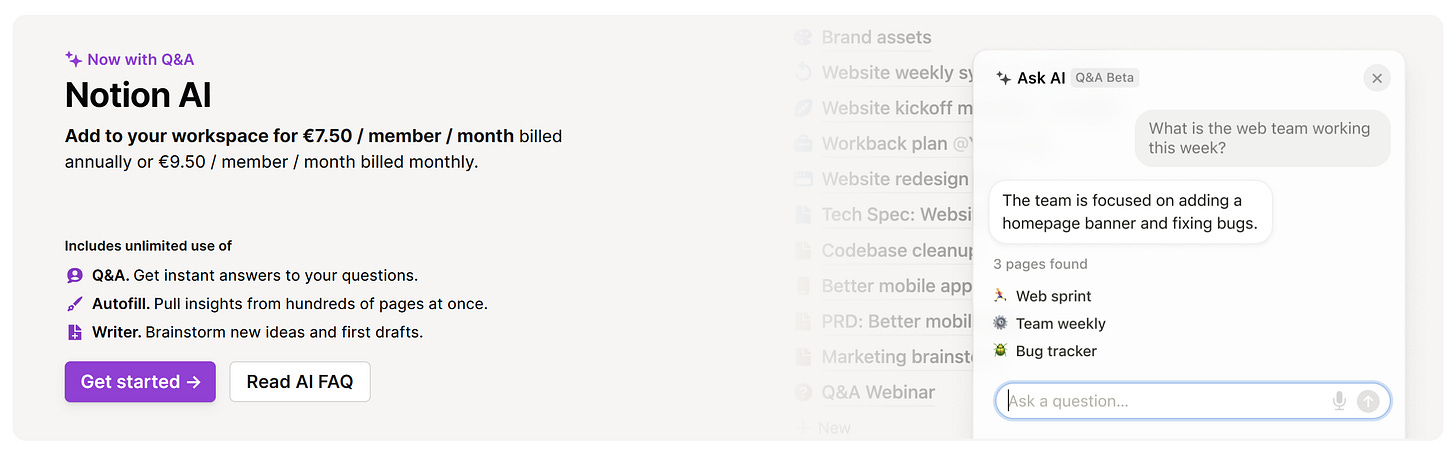

An app company, for example, can calculate the average amount they anticipate their users using the feature they are building and ration its usage to limited amounts or only to paid users. Two apps that I use that offer OpenAI services in their apps are Notion and Quizlet. They offer it in highly limited capacity to their free users and in near-unlimited capacity to their paid users.

Though Quizlet and Notion both use OpenAI’s GPT API, where they purchase access per token, they charge users on the same subscription model a subscription. I presume that the average Quizlet subscriber uses it only a few times a week, and probably most don’t at all. The majority can pay the power users who put in hundreds of requests a day.

The ad-based model

One of the problems with the ad-based model that has provided free services for the past decade is that apps offering AI services are incentivized to make their products less engaging. Consider a service like Netflix. Netflix has spent years perfecting its compression algorithm to serve you medium-quality video at an extremely low cost. Their ideal customer signs up for their most expensive plan and never logs in. However, the cost of the user who buys a plan and watches a few episodes a month generates only pennies less. Additionally, highly engaging a user on their middle-tier plan is better than not, because it increases their chances of upgrading to the high-tier one. Furthermore, their ad-based plan is a better incentive structure. With an ad-supported user, Netflix wants to balance their desire to hook a user to the app as much as possible, while making them faithful in the long-term.

It should go without saying that the goal of an app designer should be to make the most engaging app possible. If a user chooses to use your app over your competitor to complete a task, it probably means that yours adds more value to their life than the competition. I certainly dislike the fact that a large portion of the population of the world is zombified by meaningless consumption of Netflix through systems such as “Auto-play” warp the mind’s decision making, but the alternative of Netflix trying to make an app where you want to close it as much as possible probably provides less net value to the world.

The distinction between the incentives for a Netflix designer and an AI app designer is the marginal cost of providing users with value.

Consider Perplexity, a recent startup out of San Francisco that was just valued at over a billion dollars. Their product, an AI chatbot designed to replace a search engine, has become my favorite app.

Their product is an AI chatbot that, at first glance, functions highly similar to ChatGPT. What it actually does is take your prompt, rewrite it into search engine queries, search them, pull the top 20-or-so sources, and feed them into OpenAI’s GPT API to give you an answer that is far more accurate, knowledgable, and provides you with high quality cited sources. It also lets you “Focus” it to only look at YouTube videos, only search academic journals, or reference real perspectives from Reddit comments.

They offer a free version that uses the GPT 3.5 API and a $20-a-month subscription that lets you choose between any of the top models to generate your answers.

Think about that for a second. Public perception is that OpenAI is lighting money on fire serving ChatGPT to hundreds of millions of users for free, even with a massive subscriber base. Perplexity is likely throwing money at OpenAI hand-over-fist serving their smaller user base through API fees. I subscribe to both Perplexity and ChatGPT, and use Perplexity way more. Doing some napkin-math, it’s not even out of the question that my Perplexity usage in raw API fees costs them more than I pay every month.

However, the big financier of the past two decades of the internet may save AI: ads.

Ads are bad for a large number of reasons. They empower large corporate conglomerates to demand censorship, encourage surveillance, and prey upon subconscious weaknesses to get people to buy things they don’t want. With the recent passing era of the internet, the harm caused by ads was outweighed by the ability to scale free services and cheap smartphones to every person in the world. With AI, equal access to these services will create just as much, if not way more value. Giving people access to intelligence for free or cheap is vitally important, and ads will make this much easier.

Fittingly, Perplexity recently announced plans to enter advertising. According to recent reports, the app’s “related questions” feed, which currently gives users three suggested follow-up questions, will in the future contain sponsored suggestions, offering a path for brands to encourage users to learn about how their product or service is related to the questions they ask.

A free version of AI supported by ads is something that I want to see. Furthermore, I would be happy to see ads on my paid Perplexity app, if it helped subsidize the product that I get from them: one that provides much more value to me than their competition.

AI could also kill ads

While there is significant indicators that ads will be needed to subsidize AI costs, there is equal reason that AI could kill advertising entirely.

Financial Times reported in April that Google is considering stepping away from ads, and instead charging for a premium AI-powered search engine similar to Perplexity.

The past few years have been precarious for the ad business. Regulators and users hate targeted advertising for its manipulative nature. The ability to rely upon ads as a source of income is in high question as ad-powered newsrooms shut down across the country.

One possible version of the AI future is one in which your AI operates your computer for you, and only shows you what’s absolutely necessary. This would mean that it browses the web for you, reads your emails, and places orders based on your instructions. In an AI-first operating system, serving ads wouldn’t be possible. The AI would be working for you, and it would filter anything you don’t want to see.

Especially as smart glasses like Meta’s Project Nazare (or Google Glass) seem to be the computing format of the future, our interfaces with computers will be less controllable by such as advertisers. Primarily because the interfaces will be much more controlled by an AI working on your behalf, but also because you could imagine having them blur out ad billboards you see in real life, because every user would want it.

The medium-term of AI will be a great era of demolition in the ways of internet, technology, economics, and everything else by proxy. A few conclusions:

AI is not an everything-glue. It will be tremendously useful in certain areas, and entirely useless in others.

People will come to AI with vastly different needs and willingness to pay.

With so many different use cases, AI models will see many different optimal pricing systems.

If there is a dominant pricing system for AI, it currently remains entirely unclear.